Music is analyzed and discussed using tools from many different fields - history, musicology, and sociology, to name a few. But words like “magical” and “mystical” rarely enter into the critical vocabulary when talking about music. Perhaps it’s because words like that tend to bring to mind the wilder, wackier reaches of the “New Age” section of the bookstore. Perhaps it’s also because “magic” and “mysticism” seem to imply that there are aspects of music that elude our critical grasp -- intangible qualities that escape the bounds of conventional analysis. For people who study music, this can be a hard pill to swallow. But musicians throughout the ages have openly referenced mysticism and mystical concepts in their work - a roster that includes everyone from composers like Alexander Scriabin and Olivier Messiaen to jazz musicians like John Coltrane and Albert Ayler to stadium rockers like Led Zeppelin.

A few months ago, after visiting the "Brion Gysin: Dreamachine" exhibition at the New Museum, I came across a dusty book in a small East Village bookshop titled Music, Mysticism and Magic: A Sourcebook, edited by Joscelyn Godwin. The book was published in 1986; the cover was purple and covered with symbols. The 61 brief chapters featured excerpts from the writings of figures ranging from Plato to the avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. I was intrigued.

After looking up more information on the book, I came across a new book with an oddly similar title: Music, Magic, and Mysticism, edited by John Zorn (Tzadik, 2010). It is the fifth installment of Zorn’s “Arcana” series of anthologies of critical writing on music, most of it written by musicians. The contributors to this volume are impressive: Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Yusef Lateef, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, David Toop, Gavin Bryars, and Alvin Curran, to name a few.

In the introduction, Zorn writes on the mysteries of the creative process - that fleeting, elusive spark that gives rise to a new work. “Described alternately as being in the zone or the flow, channeling the muse, self hypnosis or the piece writing itself, the feeling is a universal yet ineffable one of being in touch with something outside or larger than oneself,” Zorn writes. “The manifestations of this can include unusually intense concentration on one’s work resulting in a lost sense of self, a merging of action and awareness…a perfect balance between ability level and challenge, a powerful sense of personal control rendering the process effortless, and often an altered or lost sense of time. Goals become so clear as to be almost absent—one exists inside the hot crucible of creativity itself, connected with a spirit, energy or historical lineage that is overpowering, exhilarating, frightening.”

The contributors to this volume address that creative process by way of their experiences with music and “mysticism,” whatever that may mean to each individual. Several contributors draw on concepts from organized religion, including Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. Others talk about physics, astronomy, and neurobiology, sometimes scientifically and sometimes, well, dreamily. William Kiesel writes on the myth of Orpheus; Alvin Curran writes on his memories of the artist and composer Takehisa Kosugi.

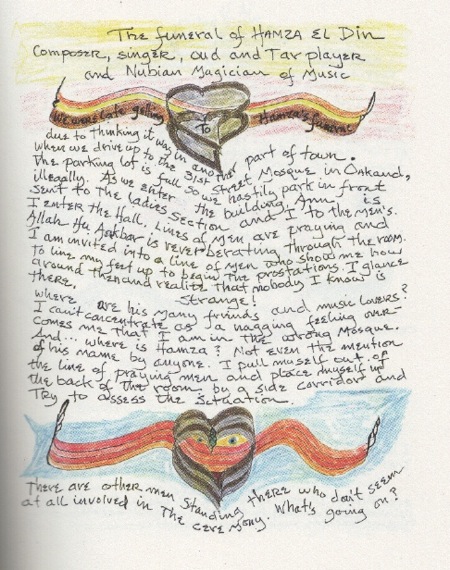

One of the most striking things about this book is how personal and revealing these musicians are, much more so than they are in their interviews in the press. The tone is conversational; it is a small-press book, of musicians writing for an audience of other musicians. Larkin Grimm, an American singer-songwriter born in Memphis, writes frankly about experimenting with medicinal plants and various psychedelics, including “a practice of taking two spoonfuls of psilocybin mushroom-laced honey every day until time and space melted away into flashes of mercury around the periphery of my vision.” Terry Riley, the famed minimalist composer best known for the masterwork “In C,” contributes a series of sketches and scrawls in colored pencil. One page simply reads: “It’s not music if there is no seduction,” with each letter drawn in a different color. Another page is a hand-drawn shrine to Pandit Pran Nath, the late guru who was a major influence on Riley, La Monte Young, and many other composers. Another page, festooned with colorful hearts, references the funeral of the Nubian musician Hamza el Din, who died in 2006. Another page advises swapping swear words for Italian musical terminology, like “mezzoforte” and “pianissimo.” Riley’s idiosyncratic chapter - if it can be called a chapter - is worth the price of the book alone.

Some other chapters of note include an impassioned essay by Meredith Monk, detailing an epiphany she had in the 1960s about the power of the human voice, and its “myriad characters, landscapes, colors, textures, ways of producing sound, wordless messages.” Fred Frith writes poignantly on his memories of working in a mental institution at age 19, and his observations of music’s power on the patients. One of the most moving and cogent chapters in the book comes from someone best known in yoga circles: Sharon Gannon, who co-founded the Jivamukti school of yoga. She is also a musician, who once played with Don Cherry in the 1980s, and possesses a strong understanding of ancient Indian scriptures and the study of sound.

The book is rich in vivid accounts of rituals and performances in far-flung places. The composer Peter Garland writes on his observations of all-night shadow puppet plays in Bali, dances of the Sufi Whirling Dervishes in Istanbul, and Zuni nighttime rituals in Zuni Pueblo, New Mexico. Tim Hodgkinson, another composer, writes memorably about his experiences with the locals of Tuva, a region of southern Siberia known for its mesmerizing practice of throat singing.

But sometimes the most far-flung place to travel is to travel inside yourself, and music provides a way to do this. As Grimm writes: “Music is a very useful and safe way to practice magic. It has been the only means of truthful communication to me in my life. It works immediately. Not like reading a book. Stop reading this … examine the world around you. You will discover that it is magical.”

Geeta Dayal is the author of Another Green World (Continuum, 2009), a new book on Brian Eno. She has written over 150 articles and reviews for major publications, including Bookforum, The Village Voice, The New York Times, The International Herald-Tribune, Wired, The Wire, Print, I.D., and many more. She has taught several courses as a lecturer in new media and journalism at the University of California - Berkeley, Fordham University, and the State University of New York. She studied cognitive neuroscience and film at M.I.T. and journalism at Columbia. You can find more of her work on her blog, The Original Soundtrack.

m: http://www.emvergeoning.com/?p=6149#comment-199356

m: http://www.emvergeoning.com/?p=5628#comment-162897