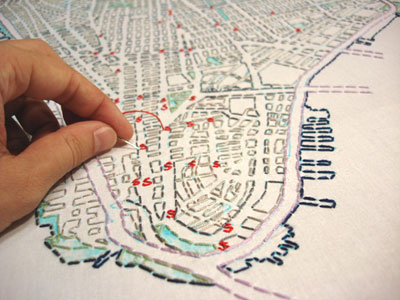

This past weekend, Barcelona-based artist Liz Kueneke offered a cloth map of Manhattan to passing downtown crowds, inviting them to sew, as roads and icons, their daily routes and personal events onto what amounted to a communal quilt. This may sound quaint in the age of Google Maps, and the legion of amateur cartographers it has created, but such a project would not exist without Google: people's lived landmarks were seldom considered of interest prior to online mapping. The implied value is that our interior, local maps are as worthy as the Mercator.

Kueneke's map, "Manhattan's Urban Fabric," formed a fraction of the cartography, art, talks, performances, and situations included in this year's Conflux, the sole arts festival devoted to psychogeography. (Conflux was at one time categorical about its subject, and was called the Psy.Geo.Conflux, but the affixes have since been dropped.) "Psychogeography" -- still a nebulous term that proceeds unrecognized by the standard dictionaries -- here encompasses a great scope of projects, from futurist utopianism and street art to anarchist rhetoric and Situationist homage. With over four hundred submissions, it is not surprising that one of the curators described the selection process as "chaotic." Another curator divided the works at the festival broadly into categories which either "read" or "wrote" the city, and further, into analog or digital creations.

Digital work and speculation about how binary code may improve urban life provide an aura of mainstream legitimacy otherwise repudiated by Conflux -- which, for its five years, has avoided corporate backing -- but this is not to say that the presence of such is disingenuous. Even the design of the festival's website speaks to this desire, as it embraces the participatory, post-it-yourself tenet wherein artists, for better or worse, compose their own descriptions of their work. In the past, the possibilities of portable gadgets have figured largely; this year, the focus was on making mute objects communicative. Architectural theorists The Living gave a talk on how they believe buildings will eventually share information through a version of social networks and on their facades, which could illustrate, say, the day's air quality index. A less fanciful example of this same impulse is Jenny Chowdhury's larky, WiFi-detecting jacket: absurd as fashion, but interesting as a magnified instance of the quotidian computer iconography we have come to ignore.

London's CutUp Collective, meanwhile, put technology to service for "intervention" -- the weekend's watchword -- rather than information. At the Conflux headquarters, they reproduced a version of their standard practice on the street, whereby they remove an advertisement from a billboard, cut it up, and reconfigure the pieces as a reflexive mosaic: automobile advertisement becomes woman in pollution mask. Sometimes, the subjects of the mosaics are indiscernible despite being meant to present distinct imagery; close up, they are always so. While this does wipe out the intended commentary, the abstraction, intended or not, is welcome in the field of street art, where the visual pun is king.

A week prior to Conflux, and under its aegis, a panel was held on urban intervention / street art at the New Museum. CutUp Collective was in attendance, as were Betsey Biggs, Leon Reid IV, and Roadsworth. The playful, Banksyan defiance found in the work of these last two artists was perhaps most indicative of the tone underlying this type of practice: Reid bends lampposts to a kiss; Roadsworth stencils barbed wire at the edges of a crosswalk and calls it "Cattle Crossing." The agenda is to offer a riposte to the city's functionalist monologue, or more precisely, monograph: the constant don't that fences, signs, and street markings assert. Street art does not yet have the agency to offer a comprehensive I will, too, so in the meantime, they take the palimpsest of the city and its symbols and give it an overdue copy edit.

The politics of street art jibe with that to which Conflux extends considerable sympathy -- namely, anarchism -- as the selection for this year's keynote speaker makes clear: Chris Carlsson, co-founder of Critical Mass and author of Nowtopia: How Pirate Programmers, Outlaw Bicyclists, and Vacant-Lot Gardeners Are Inventing the Future Today. (In 2004, new age anarchist Hakim Bey, who gave us the "Temporary Autonomous Zone," or TAZ, neologism, presented at Conflux, and his work is still generating ideas there.) Carlsson argued strongly for the subversive ethic that Conflux engenders, one that coincides with the subject of his book, and maintained that an admirable feat of the festival lies in its creation of a decommodified social space in prime Manhattan. He also framed the artwork undertaken as explicitly in opposition to the spectacle.

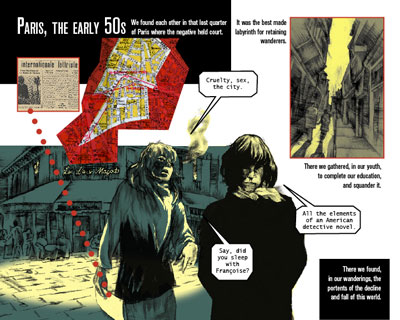

Certainly, this struggle against the predomination of the spectacle, a Situationist idea, was a theme amongst many of the works included in Conflux. Some of the projects, like Near Future Laboratories' "Drift Deck," a pack of cards meant to aid in a successful dérive, were evidently still in a first flush of exposure to the Situationists' powerful theories and strategies -- spectacle, détournement, situations, dérive, and, of course, psychogeography. McKenzie Wark and Kevin Pyle continued this lineage in their presentation of the comic book, Totality for Kids, which takes lines from comics that the Situationist International détourned in the 1960s and puts them into new graphic form as a history of the early days of the Situationists. After their talk, Wark and Pyle were justly charged by the audience of performing precisely the type of recuperation that the Situationists sought zealously to avoid, and they defended themselves by arguing that Guy Debord was an arch-romanticist himself.

The Situationists had hoped to dye the Seine red; it would have been a grand, radical gesture, bigger than Olafur Eliasson's The New York City Waterfalls, and entirely unsanctioned. One complaint that could be leveled against Conflux is that its events are never grand; rather, they can be trivial, or limited by a New York-specificity. But the festival is changing. Christina Ray, the founder, has announced that this may be her final year as organizer. She has brought Conflux from the Lower East Side's ABC No Rio, a punk club, to the West Village's Center for Architecture, a posh institute: an uptown trajectory in bona fides, if not latitude. Conflux could, at this point, embrace the monumental -- they could dye the East River -- and become a large festival, something for the masses, but they would probably need corporate money to do so in New York. Or they could embrace the parochial, which is not a pejorative when it comes to psychogeography (where deep localism is an asset), and, like Critical Mass, open up the Conflux franchise. There was a "Provflux" in 2005 -- a Conflux in Providence, Rhode Island. Why not Philadelfluxes, San Franfluxes?

Patrick Ellis lives in Brooklyn and works in publishing. He is a regular contributor to the Magazine électronique du Centre international d'art contemporain de Montréal and recently reviewed "The Cinema Effect" exhibition for Vertigo.

Artists Meeting did a number of projects for conflux 2008 in the financial district. These were done in the (POPS) corporate plazas as a way to take back public space and/or recuperate it from the Bush 9/11 protection racket years. Since we were out in the field we didn't get to many other artists works and missed McKenzie's speech. We did however set-up a system where we did the interventions and then immediately uploaded them to youTube.

http://www.youtube.com/profile_play_list?user=ghovagimyan