In his book, Parables for the Virtual, Brian Massumi calls for "movement, sensation, and qualities of experience" to be put back into our understandings of embodiment. He says that contemporary society comprehends bodies, and by extension the world, almost exclusively through linguistic and visual apprehension. They are defined by their images, their symbols, what they look like and how we write and talk about them. Massumi wants to instead "engage with continuity," to encourage a processual and active approach to embodied experience. In essence, Massumi proposes that our theories "feel" again. "Act/React," curator George Fifield's "dream exhibition" that opened at the Milwaukee Art Museum on October 4th, picks up on these phenomenologist principles. He and his selected artists invite viewer-participants to physically explore their embodied and continuous relationships to each other, the screen, space, biology, art history and perhaps more.

Fifield is quick to point out that all the works on show are unhindered by traditional interface objects such as the mouse and keyboard. Most of them instead employ computer vision technologies, more commonly known as interactive video. Here, the combined use of digital video cameras and custom computer software allows each artwork to "see," and respond to, bodies, colors and/or motion in the space of the museum. The few works not using cameras in this fashion employ similar technologies towards the same end. While this homogeneity means that the works might at first seem too similar in their interactions, their one-to-one responsiveness, and their lack of other new media-specific explorations -- such as networked art or dynamic appropriation and re-mixing systems -- it also accomplishes something most museum-based "state of the digital art" shows don't. It uses just one avenue of interest by contemporary media artists in order to dig much deeper into what their practice means, and why it's important. "Act/React" encourages an extremely varied and nuanced investigation of our embodied experiences in our own surroundings. As the curator himself notes in the Museum's press release, "If in the last century the crisis of representation was resolved by new ways of seeing, then in the twenty-first century the challenge is for artists to suggest new ways of experiencing...This is contemporary art about contemporary existence." This exhibition, in other words, implores us to look at action and reaction, at our embodied relationships, as critical experience. It is a contemporary investigation of phenomenology.

Near the entrance of the show, Scott Snibbe's Boundary Functions (1998) begins by literalizing the fine line between publicly constructed and personally constituted space, between "you (plural)" and "me." As his audience members cross the threshold onto the interactive platform, the work draws and projects a real-time Voronoi diagram around them. No matter how many people are present (and moving) in the installation, each gets a continual partitioning of exactly the same size: lines that separate them. Snibbe says his initial inspiration for the work came out of a desire to reveal how we relate to one another, how we define ourselves and the physical space of our bodies through, and with, those around us. When he turned it on, however, his revelation wound up changing that relationship itself: we immediately want to use our bodies to trap or destroy or trick the piece and what it re-presents. It was after seeing his own creation in action that Snibbe began referring to himself as a "social artist" -- given that he doesn't just reveal, but actually affects, social behavior.

Further into the exhibition space, this is followed by Snibbe's Deep Walls (2003), where viewers' shadows are recorded and played back in a grid of sixteen cinematic squares. Participants dance and shake and explore with their shadows between the projection and screen, and every active performance snippet is stored as a silhouetted animation in one of its comic book-like boxes. Each video sequence replaces one that was there before. Here, we are creating embodied and dynamic signs within a greater, collaborative structure; we continuously find and make our own language and meaning with and through our bodies. We tell and re-tell and co-tell embodied stories, through movement.

Echo Evolution (1999) is the next work on show, produced by Liz Phillips, an artist effectively working with interactivity for 40 some-odd years. It asks for viewers to navigate through a large dark room, and responds with real-time noise and neon lights. Where you move, how quickly you do so, and where others are in relation to you and the space, all direct the piece's output. Although potentially the richest piece in its complexity, the non-transparency of the interaction and its rules unfortunately made this work the weakest on the exhibition. Most viewers were trying to understand how it worked, rather than exploring their bodies in relation to that interaction. I've seen far better installations by Phillips, and think this one was an ineffectual choice in the context of the greater show.

Brian Knep's premiering Healing Pool (2008) continues his explorations of biologically inspired generative algorithms. This room-sized petri dish features a floor that is covered in projected "cells" that active participants walk through/over, leaving tears and empty space in their wake. The installation then "heals" itself by growing new cells as seams and scars, never again to repeat any of its previous patterns. Knep's work pushes at the conceptual boundaries of how we understand growth, healing, organic structures and temporal inter-activity. It's a work that is mostly playful on its surface, and extremely subtle in its visual difference over time. So subtle, in fact, that it's very easy to miss its doubled gesture towards emergence theory: both how simple systems can create complexity, and how our embodied interactions, which seemingly change little, have lasting and forever-changing effects.

Daniel Rozin's two pieces were admittedly the most surprising for those already familiar with his work. His investigation of material mirror metaphors began in 1999 with Wooden Mirror, where over 700 individual wood chips in a grid point up and down on servo motors, towards and away from lights above, in order to create a real-time video image, a live woodcut. In the preview images of "Act/React," his Peg Mirror (2007) and Snow Mirror (2006) looked like minor variations on this original theme: the former in lower resolution and with rotating and slanted wooden pegs, the latter a video software projection which slowly reveals our images in what looks like falling snow. But the subtle temporal difference in Rozin's new work opens up the possibility for more contemplative embodied investigation. In Peg Mirror, for example, the slow rotation of each individual pixel means that there is a lovely and material lag that trails off behind everything we do. It is less of a direct response, and more of a call and response with our reduced, or distilled, image. Our engagement is continuous. Snow Mirror, then, also breaks direct mirroring by building an image over time, with "external" forces -- the snow. Its movements define our movements, and vice versa. These beautiful pieces are the strongest I've seen from Rozin yet.

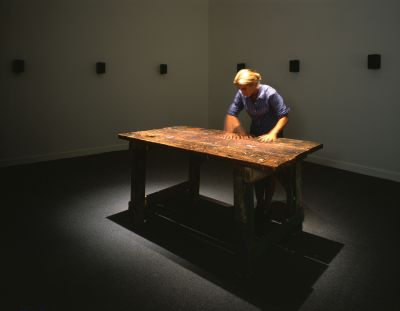

Next, Janet Cardiff's To Touch (1994) adds a wonderful counterpoint to Snibbe's Deep Walls. Instead of her visitors constituting new narratives with their bodies, they elicit and construct two lovers’ stories with their physical touch. Each participant is invited to draw out and feel monologues and aural moments, her main characters revealing history when we glide over the surface of a well-lived carpenter’s table. As our hands caress the grain, marks and dents of the wood, her multi-channel sound installation proffers tidbits of story to contemplate. Cardiff is a master at creating physiological responses to minimal sonic and/or visual information, and this piece is no exception.

And finally, Camille Utterback's External Measures (2003), Untitled 5 (2004) and Untitled 6 (2005) summarize the entire show by inviting an embodied investigation of art, art history and art-making itself. Here, visitors' movements under a birds-eye view camera can create, smudge or magnetically and magically attract scores of painterly marks across her screen-as-canvas. These stunning software paintings each encourage explorations of material and presence, with varying styles and application methods to their surface. The complexity of Utterback's software, which is crafted to respond to stillness as well as movement, to continuously shift with every new interaction, is matched only by the simplicity of her interface: the body. This is art about art and artists, images and image production, signs and bodies; it asks us to engage with how we express and represent, and how we relate to each of these embodied processes. It is a beautiful series of works about the art of embodiment, and the embodiment of art.

For as Massumi points out, "When a body is in motion, it does not coincide with itself. It coincides with its own transition: its own variation... In motion, a body is in an immediate, unfolding relation to its own... potential to vary." The body, like art and the bodies and dialogues that surround it, is "an accumulation of relative perspectives and the passages between them... retaining and combining past movements," continuously "infolded" with "coding and codification." Fifield and his selected artists invite us to engage, enact and explore all of the above.

"Act/React" runs through January 11, 2009 at the Milwaukee Art Museum, and includes a full-color printed and DVD catalogue, in collaboration with Aspect Magazine. Remaining events include a lecture by Steve Dietz on 16 October, an artist talk by Amy Granat on 13 November, and gallery talks throughout the rest of the year. http://mam.org/

Nathaniel Stern (USA / South Africa, born 1977) is an experimental installation and video artist, net.artist, printmaker and writer. He currently pursues an arts research PhD at Trinity College, Dublin and is an Assistant Professor of Digital Studio Practice at the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee. http://nathanielstern.com

it is probably a good show, but it's been a long time since i read such eloquent and fluid review. great!

thanks, maja. glad you like it.